How do you add fractions?

Probably in school you learned that

\[\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d} = \frac{ad+bc}{bd}.\]When I was an undergraduate, a professor asked me why fraction addition had this rather funny looking definition. Why not just define it this way?

\[\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d} = \frac{a+c}{b+d}.\]Well, obviously, because this doesn’t work. If I buy a pizza, give my mother half of it, and my father a quarter, well, I’ve given away three-fourths of the pizza, not one-third. What a silly question!

But an answer like this misses the point of the question. The method you learned in school works, that is clear. But why does it work? What’s happening behind the scenes? Such questions point to icebergs: visible, accessible instances of deeper phenomena. There are many lovely ideas lurking beneath the surface. Let’s dive in.

To begin, we need a good definition of what “fraction” means. After all, if we are to be adding these objects, we should know what they are in the first place. Imagine you are seven years old again. You are perfectly happy with your numbers, \(1\), \(2\), \(3\),… maybe even \(0\) and \(-1\), \(-2\), \(-3\),… but soon enough, your teachers will make your life difficult by introducing fractions. Why do they do this?

Well, the concept of fractions is motivated by a simple problem. At age seven, all the numbers you know look like the ones above (integers). Then someone comes along and asks you: what number do you multiply \(5\) by to get \(1\)? Umm… there’s no such number, as far as you know. That’s true—there’s no such integer.

This is unsatisfying. We would like to have such a number, for any one of your favourite reasons: “it would have practical application”, or “it bothers me that there’s no such number”, or “more numbers? Yay!”

So we introduce such a number: \(\frac{1}{5}\). And we say that \(\frac{5}{1} \times \frac{1}{5} = 1\). Okay, reasonable. Replacing the \(5\) and \(1\) from earlier with arbitrary integers, we get a whole new family of numbers, that look like \(\frac{a}{b}\), where both \(a\) and \(b\) are integers, and \(b\) is not zero. We call these fractions.

At the beginning, we had with us the set of all integers (denoted \(\mathbb{Z}\)), and in trying to answer the question above, we have thrown in a whole new family of numbers. Now we have with us the set of all fractions (denoted \(\mathbb{Q}\)). Observe two things.

First, every integer is a fraction (in notation, we write \(\mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{Q}\)), since any integer \(n\) can be written as \(\frac{n}{1}\). Second, in going from \(\mathbb{Z}\) to \(\mathbb{Q}\), we have thrown in multiplicative inverses for all the non-zero integers. That is, for every non-zero integer \(n\), we have a fraction, namely \(\frac{1}{n}\), that has the property \(\frac{n}{1} \times \frac{1}{n} = 1\). This is what we have done.

Now, to make good use of these fractions, we will need a way to add and multiply them. Let us say for now that there is some way to make sense of “addition of fractions”, but we don’t know exactly what it is.

But is this the only way to do such a thing? Ideally, yes! It would be quite disastrous if there were hundreds of different ways to endow integers with multiplicative inverses. And hundreds more different procedures to add them together. Then we would have to make a choice each time we wanted to use fractions, and check if different choices gave different results, and keep track of all these things, ugh…

Here is the key point. We would like the following procedure to be, in a sense, “fundamental”: endowing integers with multiplicative inverses and performing arithmetic with these inverses. And I claim that to achieve this, we have to add the fractions \(\mathbb{Q}\) the way you were taught in school.

Reformulating this in the language of algebra, we have a ring homomorphism (a function that preserves addition and multiplication, and takes \(1\) to \(1\))

\[i: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow \mathbb{Q},\]that takes every non-zero integer to a fraction that possesses a multiplicative inverse. Here, \(i\) takes the integer \(5\), which has no multiplicative inverse in the set \(\mathbb{Z}\), to the fraction \(\frac{5}{1}\), which has a multiplicative inverse in the set \(\mathbb{Q}\), namely \(\frac{1}{5}\).

Now, if there was another way to make fractions, we would similarly have a ring homomorphism

\[f: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow S,\]where \(S\) is some set, such that \(f\) takes every non-zero integer to an element of \(S\) that had a multiplicative inverse in \(S\).

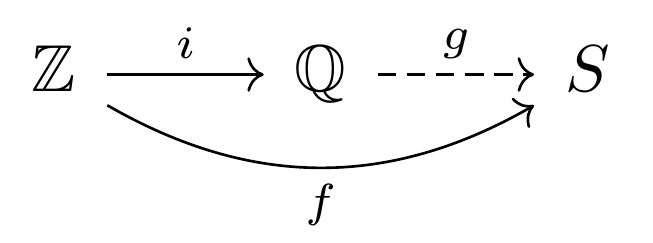

We want \(i\) to be “fundamental”, that is, we would like to have a ring homomorphism \(g: \mathbb{Q} \rightarrow S\) that makes the following diagram commute:

That is, if we do \(i\) first, and then we do \(g\), that is identical to just doing \(f\).

This will tell us that any other way of endowing \(\mathbb{Z}\) with inverses (i.e. doing \(f\)), is essentially just “an extra step” taken after endowing it with inverses elementary-school-style (i.e. doing \(i\)). In order for the elementary-school-fractions to be fundamental, we need this \(g\) to be a ring homomorphism, that is, we need it to preserve addition and multiplication of objects in \(\mathbb{Q}\), and send \(1\) to \(1\).

This is the key.

So suppose \(f(n) \in S\) has a multiplicative inverse for every nonzero integer \(n\). For the diagram to commute, we would need \(g\left(\frac{n}{1}\right)= f(n)\). This tells us the form \(g\) must take on fractions that look like \(\frac{n}{1}\). But what about arbitrary fractions \(\frac{a}{b}\)? We claim that we can let

\[g\left(\frac{a}{b}\right) = f(a) \times (f(b))^{-1}.\]Observe that this definition of \(g\) gives us \(g\left(\frac{n}{1}\right) = f(n)\), since \(g\) must take \(\frac{1}{1}\) to the element \(1 \in S\). Thus, since we require \(g\) to preserve addition,

\[g\left(\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d}\right) = g\left(\frac{a}{b}\right) + g\left(\frac{c}{d}\right) = f(a) \times (f(b))^{-1} + f(c) \times (f(d))^{-1}.\]Now a trick: on the right-hand-side, multiply by \(f(d)(f(d))^{-1} = 1\), and then by \(f(b)(f(b))^{-1} = 1\). This yields

\[\left(f(a) \times (f(b))^{-1} + f(c) \times (f(d))^{-1}\right) \times (f(d)(f(d))^{-1}f(b)(f(b))^{-1}).\]Multiplying by just \(f(d)f(b)\) first, this equals

\[\left(f(a)f(d)+f(b)f(c)\right) \times ((f(b))^{-1}(f(d))^{-1}).\]Next, using the fact that \(f\) preserves addition and multiplication, we can write this as

\[f(ad + bc) \times (f(bd))^{-1}.\]Which may look familiar. This item equals \(g\left(\frac{ad+bc}{bd}\right)\), by the definition of \(g\). And \(g\) will be one-to-one, telling us that \(\frac{a}{b}+\frac{c}{d}\) must be equal to \(\frac{ad+bc}{bd}\).

Now is this the answer to the question: why do we add fractions in the funny way? No, of course not. The answer to that is simply: it works. Indeed, we could have just done the “multiply by \(1\)” trick on \(\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d}\) and shown that it gives \(\frac{ad+bc}{bd}\).

Then why do all this? To explore something we usually take for granted, and try to understand it in a more universal way, as a specific instance of a general idea.

The generalisation of this idea is called localisation. In our basic example, it proves that fraction addition has this universal property, a cornerstone theme in mathematics.

But more generally, we may begin with some arbitrary commutative ring, and only wish to endow some elements with multiplicative inverses. (In our example, we began with \(\mathbb{Z}\), and gave every non-zero element a multiplicative inverse). Localisation deals with the technical details and consequences of this procedure. When applied to rings of functions, it provides a tool to study geometric surfaces “locally”.

In fact, it turns out to be extremely important in math, particularly in commutative algebra and algebraic geometry. Like many mathematical ideas, it has broad applicability and deep scope, despite being motivated by a very simple question: how do you add fractions?